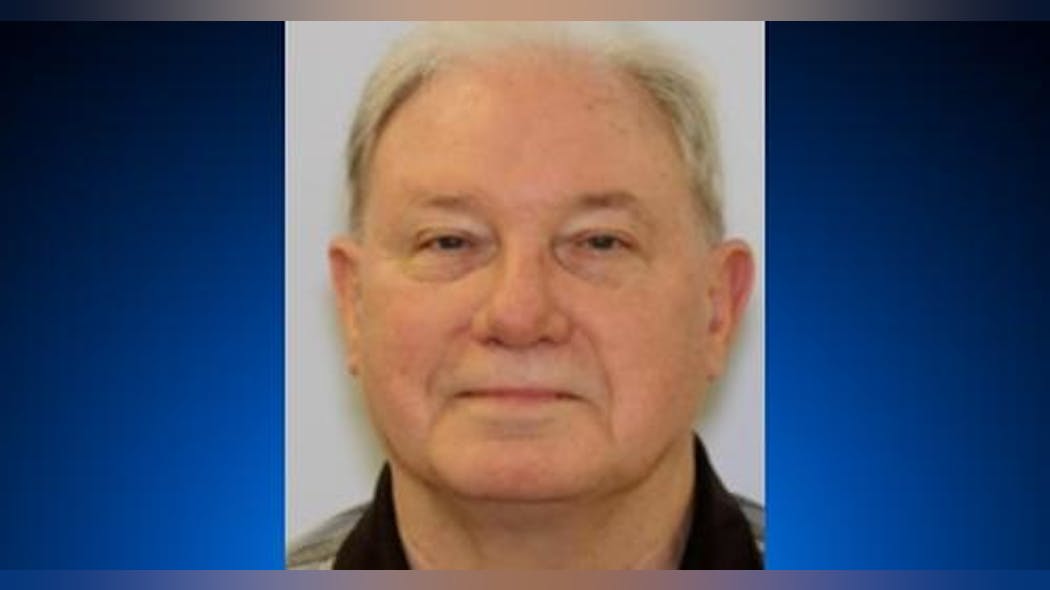

March 9, 2023 Ex-Laurel Police Chief David Crawford set fires in six counties targeting colleagues he thought were slighting him.

By Alex Mann Source Alex Mann Baltimore Sun (TNS) Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

A multi-jurisdictional investigation that linked a retired Maryland municipal police chief to a decade-long string of arsons statewide passed its first test Thursday, with a Howard County jury finding him guilty of setting four fires there.

David Michael Crawford, 71, was convicted of eight counts of attempted first-degree murder — one charge for each of the people home during fires in Elkridge and Ellicott City — three counts of first-degree arson and one count of malicious burning.

Howard County State’s Attorney Rich Gibson said his office would seek to have Crawford, a career policeman, punished with more than eight life terms in prison at his June 27 sentencing.

“This person should have been a guardian and a protector, but instead he was a menace,” Gibson said.

Authorities allege Crawford is responsible for setting a dozen fires in six counties from 2011 and 2020, targeting people who he perceived to have slighted him in matters both personal or professional.

The state typically isn’t allowed to tell the jury about crimes other than the one a defendant is standing trial for, but Howard County prosecutors said they needed to put on evidence from the string of arsons to prove Crawford set the fires in their jurisdiction in 2017 and 2018. A judge granted their request to show evidence from the other fires.

Nine people whose houses or cars were set ablaze testified at Crawford’s Howard County trial, along with fire investigators from other jurisdictions. Pictures and videos of the fires revealed a pattern: The arsonist always struck in the dark, between 1 and 4:30 a.m. He arrived in a silver sedan, poured gasoline onto his targets and set houses, garages or cars ablaze.

The victims had something else in common: All were named in a coded list police found on Crawford’s phone — an index used to keep a tally of the number of fires he set at his targets’ properties. He typed the number three, for example, next to his stepson’s name and allegedly put flame to the stepson’s property as many times.

“Ladies and gentlemen, you are looking at the defendant’s criminal resume,” Assistant State’s Attorney Patricia Cecil told the jury in closing arguments.

The jury rendered its verdict after deliberating for about five hours. Crawford’s trial spanned a week, with the state and defense submitting hundreds of pieces of evidence.

In March, Crawford entered an Alford plea — maintaining his innocence, but conceding there was enough evidence to convict him — to arson in Frederick County. He has pending charges in Montgomery and Prince George’s counties.

Crawford’s “reign of terror,” as Cecil put it, began months after he was forced to resign as Laurel police chief, with the first arson targeting the city administrator who oversaw the police department.

He arrived at Martin Flemion’s property in Laurel around 1:30 a.m. May 28, 2011, according to prosecutors. He doused Flemion’s city-issued Ford Explorer and personal car with gasoline but caught fire himself while igniting the accelerant, and was only able to set the Explorer afire.

Crawford’s injury proved to be a compelling piece of circumstantial evidence at trial.

Police raided Crawford’s house in Ellicott City in 2021, recovering troves of digital evidence from his computers, hard drives, tablets and cell phones. On one device, investigators found a post to a medical forum 17 days after the fire outside Flemion’s house. Crawford wrote that he was treating an approximately two-week-old burn to his calf.

“when i stand and do not move the leg, it feels like it is burning. when does that discomfort go away?” he asked in the online post.

Ten years after the fire, a scar remained on the lower part of Crawford’s left leg.

At trial, defense attorney Robert Bonsib did not challenge that any of the fires were intentionally set but argued the state hadn’t proven his client ignited them. He also downplayed the significance of the blazes at occupied homes, saying the arsonist hadn’t intended to kill anyone.

After the verdict, Bonsib said Crawford would appeal.

“Whenever a prosecutor is allowed to put 12 different incidents before a jury, it’s a very challenging matter,” Bonsib said. “Mr. Crawford, during his career in law enforcement, was well liked and did well, and it’s very sad ending to that career.”

No physical evidence — DNA, fingerprints, hair fibers — tied Crawford to the arsons. Instead, prosecutors relied on his digital footprint.

Crawford’s internet history showed he looked up his targets’ addresses before striking. He made calendar appointments marking the dates of some fires. He searched for news articles about the crimes after. When he knew the victims, he reached out to them or their neighbors asking for details.

“There’s your fingerprints,” Assistant State’s Attorney Scott Hammond said of the digital evidence.

Some people whose properties burned testified to small disagreements, or strained relationships, with Crawford. Others, like his chiropractors, whose Elkridge house Crawford set ablaze with the the couple, their children and a relative inside, couldn’t even think of any tension with him. Crawford’s stepson suspected him after the first fire at his house.

Evelyn Henderson testified that she worked with him on a Howard County school redistricting initiative she spearheaded in their Ellicott City neighborhood. The morning after she interrupted him at a big community meeting, Crawford sent out an organizational flow chart of their committee placing Henderson at the bottom.

Months later, she woke up in the middle of the night to a smoke-filled bedroom and a garage fire that reeked of gasoline. Her husband and daughter were home at the time.

Crawford maintained friendly contact with the people whose properties he burned. Whether it was under the pretext of trying to avoid a fire in his own garage or offering to help investigate the arson, Crawford asked about the cause and origin of each blaze.

“Arson is one of the most difficult crimes to solve,” Justin Scherstrom recalled his stepfather telling him after each of the three fires at Scherstrom’s properties.

Henderson said redesigning the house was her family’s way of coping with their loss.

Once they started to rebuild, Crawford kept tabs on the construction.

In September 2018, Henderson asked for help on social media getting power restored to their almost-rebuilt home. Crawford responded to her post.

About a week before the family was supposed to move back in, the house was burned down. It was completely destroyed.

The Hendersons were among the arson victims who packed the courtroom awaiting the verdict. Arson investigators from around the state who in 2019 finally recognized a connection between what for years seemed liked random and unrelated fires watched, too.

Crawford’s daughter, who accused her father of terrorizing her for years to get custody of her child, sat through the entire Howard County trial. Carrie Turner said the verdict made her feel “vindicated.”

“My dad used to say ‘many hands make light work,’” Turner said. “In this case, many hands make justice work.”