April 14, 2023 Firefighter Frank Bolden, who wasn’t allowed to sleep or eat with white colleagues, retired as assistant chief..

By Shaddi Abusaid Source The Atlanta Journal-Constitution (TNS) Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

When Frank Bolden became one of Atlanta’s first Black firefighters six decades ago, he wasn’t allowed to eat with his white colleagues, sleep in the same room or drive the big truck to emergency calls.

When the city integrated its police force 15 years earlier in 1948, the first eight Black officers had to change clothes in a separate facility. They worked only at night, patrolled only African American neighborhoods and arrested only people with the same skin color.

Things have changed drastically since then. Today, most of Atlanta’s police officers and firefighters are Black, much more representative of the city they serve.

But that wouldn’t have been possible if not for the public safety pioneers who broke the color barrier and helped pave the way. Those trailblazers were recently recognized for their contributions to the city.

As proud as Bolden was to become a firefighter, he quickly realized not everyone was thrilled to have him around.

“There were a lot of things we couldn’t do that other firefighters could,” said Bolden, who was among 16 Black firemen hired by the city in 1963. “But we were not gonna quit.”

It would be another 14 years before the city hired its first group of Black women firefighters, who came to be known as the “Magnificent Seven.”

Things got better with time, said Bolden, who is now 82. He quickly earned the respect of his white counterparts at Station 16, some of whom took him under their wing. He served for 32 years, reaching the rank of assistant chief before retiring in 1994.

Liz Summers initially had no desire to become a firefighter.

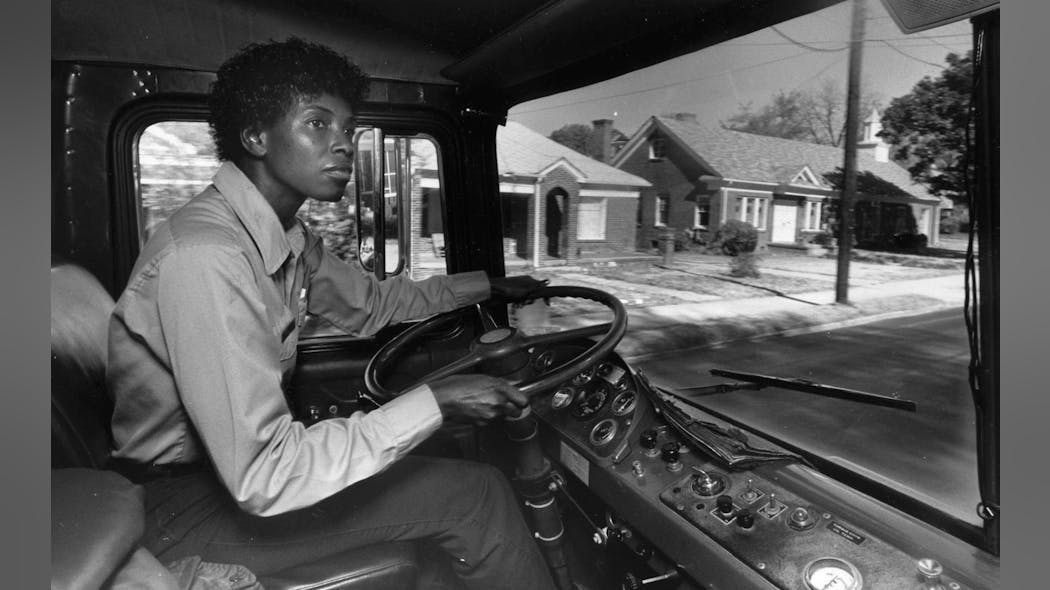

In the 1970s, the West Point native spent time working as a schoolteacher and basketball coach. She hoped to become a police officer, and even drove a police van while waiting for the city’s hiring freeze to be lifted. Then she found out the fire department was hiring and was encouraged to apply. It was a move that shaped the rest of her life.

Having worked in male-dominated industries before, Summers didn’t think much about making history at the time. Then she went to a firefighters’ convention the following year and everyone wanted to take her picture.

“It wasn’t until later on that I realized we were doing something special,” the 76-year-old told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

For Summers, fighting fires became a family business. Her son, Irving Reese, later joined the department and the two became the nation’s first mother-son firefighter duo, she said.

Summers spent 32 years with the department, reaching the rank of battalion chief. Her son retired as a captain.

Atlanta fire Chief Rod Smith said his department wouldn’t be what it is today if not for the courage of the Original 16 and Magnificent Seven.

“They faced discrimination, segregation, but never wavered in their commitment to serve the citizens of Atlanta,” Smith said. “Their bravery and dedication paved the way for all firefighters of color who followed in their footsteps, including myself.”

Atlanta’s first eight police officers also had a tough time. Many had served their country valiantly in World War II only to return home to the segregation and racism they’d known all their lives. The decision to integrate the police department was a political one, said Mayor Andre Dickens. Then-Mayor William Hartsfield faced a tough reelection bid and needed to win over more Black voters to remain in office.

The city council vote to hire Atlanta’s first Black officers was close, with city leaders eventually approving integration by an 8-7 margin.

At a public hearing before the vote, residents argued both for and against integrating the department, said police Chief Darin Schierbaum, who read through the old meeting minutes.

Those speakers’ names and sentiments were entered into the official record, but the clerk at the time quoted only one person directly: the Rev. Martin Luther King Sr., the pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church and the father of the civil rights icon.

The elder King told city leaders that “the hour and the time is now for change, advancement and courage.”

At a ceremony honoring those first hires, Schierbaum told the gathered crowd, “It was the oratory of courage from pulpits, from front porches and from community organizations that encouraged eight men to take that oath in service to this city.”

Descendants of the first Black officers were among those in attendance. They looked on proudly as city leaders praised their relatives for what they endured.

Tamaira Lyons, the granddaughter of Ernest Lyons, described him as a tough guy with a larger-than-life personality. He died in 2000 at the age of 80.

Lyons faced plenty of challenges as one of the first Black officers, including being called racial epithets by white members of the force. But the city’s Black community was proud of its officers, and Lyons developed deep ties with the residents on his beat, his family said.

“He loved the city and he loved being a police officer,” said Tamaira Lyons, who attended the event with five of her sisters. “But it’s amazing to think about how much has changed since then.”

Before joining the department, Ernest Lyons was a member of the Montford Point Marines, the nation’s first Black Marine regiment based in North Carolina. He would go on to become one of the city’s first Black detectives.

Lyons stayed involved even after his retirement. He worked part time for the city’s school system and later served as an honorary officer when the Olympics came to town in 1996.

“He was just a kid growing up in the Jim Crow, racist South,” his granddaughter said. “In becoming one of the first Black officers, he went on to fulfill a dream he had when he was just 9 or 10 years old.”